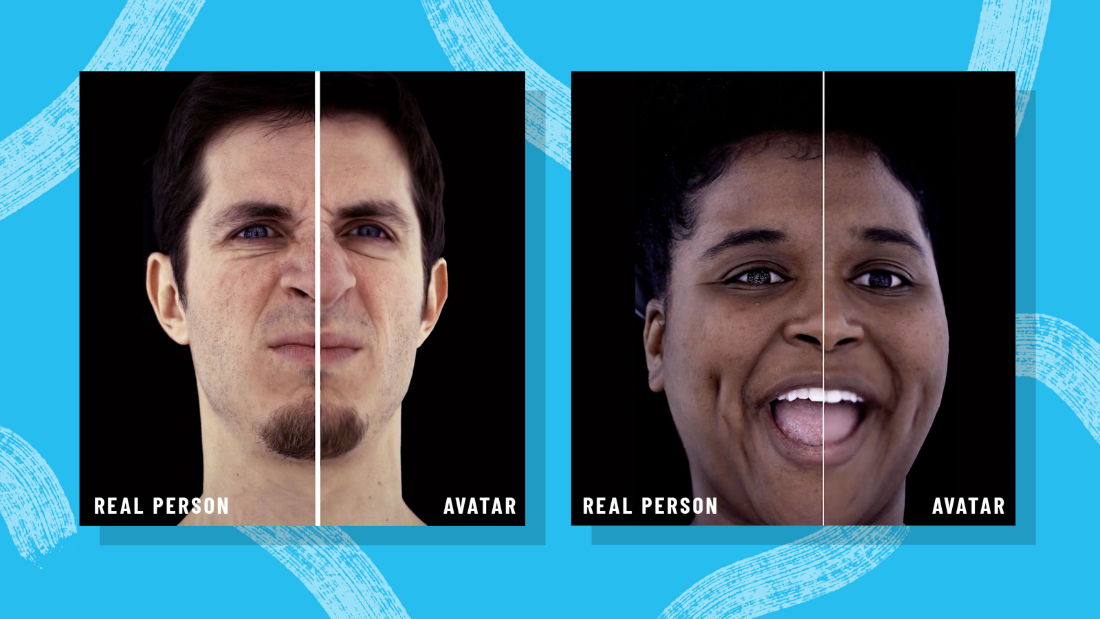

As Meta (facebook) researches, the new Meta Codec avatars are nearly indistinguishable from the humans they portray, and could become a staple in our virtual lives in the metaverse sooner than we think.

The Metaverse: A New Frontier for Avatars

As Meta (formerly Facebook) continues to develop its vision for the metaverse, one of the most important aspects of the project is the development of avatars. Avatars are digital representations of ourselves that we can use to interact with others in the metaverse. They can be anything from simple cartoon characters to highly realistic representations of our physical bodies.

Meta's Codec Avatars are a new type of avatar that is being developed by the company's VR/AR research arm, Reality Labs. Codec Avatars are designed to be highly realistic, with features that are indistinguishable from those of real people. They can express a wide range of emotions, and they can even be customized to look like the user.

The development of Codec Avatars is a significant step forward for the metaverse. Avatars like these have the potential to revolutionize the way we interact with others online. They could make it easier for us to connect with people from all over the world, and they could help us to build stronger relationships.

Of course, there are also some potential challenges associated with the use of avatars in the metaverse. For example, some people may be concerned about the potential for avatars to be used to create fake identities or to spread misinformation. It is important to be aware of these challenges, and to take steps to mitigate them.

Overall, the development of Codec Avatars is a positive step for the metaverse. Avatars like these have the potential to make the metaverse a more inclusive and engaging place. They could help us to connect with others in new and meaningful ways, and they could help us to build a better future for ourselves and for the world.

Here are some additional thoughts on the potential impact of avatars in the metaverse:

- Avatars could help us to overcome physical barriers and connect with people from all over the world.

- Avatars could help us to build stronger relationships by allowing us to express ourselves in new and more creative ways.

- Avatars could help us to learn and grow by providing us with new experiences and perspectives.

- Avatars could help us to be more productive by allowing us to work and collaborate with others in a more immersive and engaging way.

The potential impact of avatars in the metaverse is vast and exciting. It is still too early to say exactly what the future holds, but one thing is for sure: avatars are here to stay.

“The goal here is to have both realistic and stylized avatars that create a deep feeling that we’re present with people,” Zuckerberg said at the rebranding.

For years now, through avatars, computer-generated characters that represent us, people have been interacting in virtual reality. Since VR headsets and hand controllers are trackable, the unconscious mannerisms that add vital texture bring our real-life head and hand gestures into those simulated conversations. Yet, even as our interactive experiences have become more naturalistic, it has forced them to remain visually simple by technological constraints.

Rec Room, roblox, microsoft mesh, and other social VR applications abstract us into caricatures, with expressions that rarely map our faces to what we actually do. Facebook's Meta Spaces can create a realistic cartoon approximation of you based on your social media images.

If avatars are truly on the horizon, we'll have to confront some difficult questions about how we present ourselves to others. What impact might these virtual versions of ourselves have on our feelings about our bodies, for better or for worse?

Of course, avatars are not a new concept. Gamers have been using them for decades: Super Mario's pixelated, boxy creatures have given way to Death Stranding's hyper realistic forms, which emote and move eerily like a living, breathing human.

When we expect avatars to act as representations of ourselves outside of the context of a specific game, however, things get a little more complicated. It's one thing to put on Mario's overalls and twang. It's another thing entirely to create an avatar who serves as your spokesperson, your representative, and your very self. The avatars of the metaverse will be involved in situations with higher stakes than a race for treasure. This self-presentation may play a larger, far more important role in interviews or meetings.

Avatars that reflect who they are could be a powerful source of validation for some people. However, creating one can be difficult. For example, gamer Kirby Crane recently conducted an experiment in which he attempted to do one simple thing: create an avatar that resembled him in ten different video games.

"My goal was more to explore the representation that's available in current avatars and see if I could portray myself accurately," says Crane, who describes himself as a "fat, gay, pre–medical transition trans man."

Some games allowed him to bulk up his body, but if he tried to make the character fat, he would burst out of his clothes. Other games didn't let you have a male avatar with breasts, which Crane found isolating because it implied that the only way to be a man was to present as one.

Crane wasn't surprised that none of the avatars felt like him in the end. "I'm not looking for validation from random game developers," he says, "but seeing the default man and the accepted parameters of what it means is dehumanizing."

Crane’s experiment isn’t scientific, nor is it any indication of how the metaverse will operate. But it offers a peek into why avatars in the metaverse could have far-reaching consequences for how people feel and live in the real, physical world.

Meta's announcement of Codec Avatars, a project within Facebook's VR/AR research arm, Reality Labs, that is working toward making photorealistic avatars, further complicates the issue. Some of the advancements the group has made in making avatars appear more human, such as clearer emotions and better rendering of hair and skin, were highlighted by Zuckerberg.

“You’re not always going to want to look exactly like yourself,” he said. “That’s why people shave their beards, dress up, style their hair, put on makeup, or get tattoos, and of course, you’ll be able to do all of that and more in the metaverse.”

Anthropologist Edward Sapir wrote in the 1927 essay "The Unconscious Patterning of Behavior in Society," that people respond to gestures "under an elaborate and secret code that is written nowhere, known by none, and understood by all." Ninety-two years later, replicating that elaborate code has become the ongoing task of Sheik.

Yaser Sheikh was a Carnegie Mellon professor before he came to Facebook, studying the intersection of computer vision and social perception. Sheikh didn't hesitate to share his own vision when Oculus chief scientist Michael Abrash reached out to him in 2015 to explore where AR and VR could headed.

"The real promise of VR," he says now, both hands around an ever-present coffee mug, "is that instead of flying to meet me in person, you could put on a headset and have this exact conversation that we're having right now—not a cartoon version of you or an ogre version of me, but looking the way you do, moving the way you do, sounding the way you do."

(In his founding document for the facility, Sheikh referred to it as a "social presence laboratory," referring to the phenomenon in which your brain reacts to your virtual surroundings and interactions as if they were real.)